The 2013 October timetable re-write is the O’Farrell Government’s greatest opportunity to fix the trains, as Transport Minister Gladys Berejiklian often chants, during its first term. The Cityrail system is currently plagued by poor reliability and rising levels of overcrowding. The latter has been caused by insufficient capacity and has become so much of a problem, that it has led to longer dwell times at stations which in turn further reduces reliability and also the maximum number of trains that can pass through those stations during peak hour. This, ironically, further reduces total capacity, which makes the problem even worse.

I’ve previously looked at how the rail system can be improved via simplifying the network. In this post I’m going to look into how to do it by increasing capacity. In particular, what has been confirmed for the 2013 timetable, and what is rumoured to be likely.

Overcrowding

Cityrail measures overcrowding twice a year in terms of passenger loads – the proportion of passengers to seats on each train (each 8 carriage train has about 900 seats). If each seat is taken, then it has a 100% load. If there are 35 standing passengers for every 100 seated passengers, then it has a 135% load. It is once you go above a load of 135% that dwell times begin to become problematic.

Actual overcrowding by line in September 2012. (Source: Cityrail)

Based average loads during the AM peak, the most overcrowded lines are the Bankstown Line (134%) and Northern Line (143%). Also high are the Airport & East Hills Line (127%), Illawarra Line (123%), Western Line (119%), and South Line (119%). These are just average loads, however, and it can be higher or lower for each individual train. So when looking at maximum loads, only 2 of the 9 suburban lines have all their trains below the 135% load – those being the Eastern Suburbs Line (which consists of only 3 stations before reaching the CBD) and the North Shore Line (which at 128% is only just below the 135% cut-off).

Spare capacity

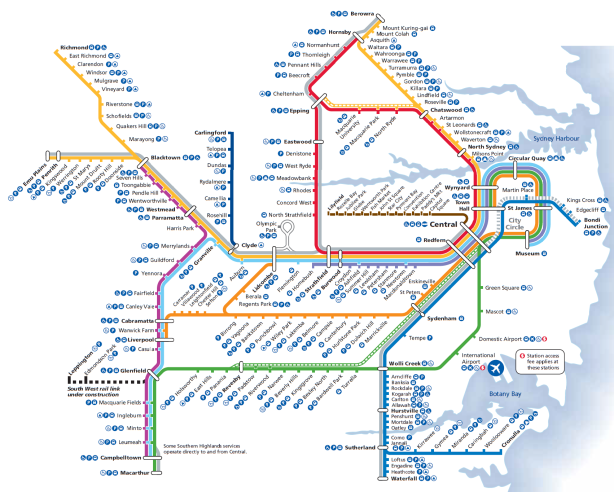

The CBD subway portion of the rail network has 3 lines (Sectors) – the Eastern Suburbs Line (Sector 1), the City Circle (Sector 2), the Harbour Bridge (Sector 3). Each of these can handle 20 trains per hour in each direction. Sydney Terminal at Central Station also provides some capacity, and currently handles 12 trains per hour during the AM peak (4 Blue Mountains, 4 Central Coast, 3 South Coast, 1 Schofields). Each of these has some spare capacity (subject to rolling stock availability).

The Harbour Bridge (Sector 1). 16 Western Line and 4 Northern Line trains enter the CBD from the South, meaning this approach is already at capacity (though the one Schofields train that terminates at Central could be extended to cross the Bridge). 18 trains from the North Shore Line enter the CBD from the North, meaning 2 additional trains can be added here.

The City Circle (Sector 2). 15 trains pass through the City Circle in both the clockwise and anti-clockwise directions. The breakdown is 7 South Line, 5 Inner West Line, and 3 Bankstown trains enter the CBD via Town Hall, while 12 East Hills & Airport Line, and 3 Bankstown Line trains enter the CBD via Museum. Trains from Bankstown can enter from either direction, providing a large amount of flexibility in how the spare capacity of 10 trains per hour is assigned.

The Eastern Suburbs Line (Sector 3). 15 Illawarra Line trains enter the CBD from the South and 15 Eastern Suburbs Line trains enter the CBD from the East. However, there are also 3 South Coast Line trains that terminate at Central which share the same track as the 15 other trains South of Central, and so there is only really an additional capacity of 2 trains per hour in each direction here.

Sydney Terminal. If the 3 South Coast Line trains are extended to Bondi Junction while the Schofields train continues across the Harbour Bridge, as mentioned earlier, then this can create additional capacity at Sydney Terminal for 4 trains an hour.

Changes in the 2013 Timetable

The Eastern Suburbs Line (including the South Coast Line) will see its capacity increased from 18 trains per hour to the maximum 20 trains per hour. Whether this is in both directions, or just from the Illawarra Line side is uncertain. The latter is likely given that trains from Bondi Junction are the least crowded in the network and probably don’t need additional services.

“two additional services [on the Eastern Suburbs Line] to be provided in the peak” – Source: Sydney’s Rail Future, p. 19

Additional services will be added to the Bankstown Line, though no figure is mentioned. However, 2 more trains per hour, increasing the current 6 to 8, seems reasonable.

“The Bankstown line will receive new services in peak times from 2013” – Source: Sydney’s Rail Future, p. 18

On the Airport & East Hills Line’s maximum capacity will be increased to 20 trains per hour, compared to the current 12 (4 express via Sydenham and 8 all stops via the Airport). However, for the 2013 timetable, it appears only an additional 4 services are being added, raising the number of services via the airport from 8 to 12, while maintaining the 4 Sydenham express services

“Sydney’s south west will see an increase in train services with the commencement of the 2013 timetable…Upgrades to the power supply and safety aspects of the Airport line will allow for services from Holsworthy, Glenfield and the South West to be doubled from the current eight to up to 16 services per hour…With the addition of Revesby services, this will allow a total of 20 services per hour through the Airport line” – Source: Sydney’s Rail Future, p. 19

“increase peak hour services to the Airport from eight to 12 per hour” – Source: Transport Master Plan, p. 313

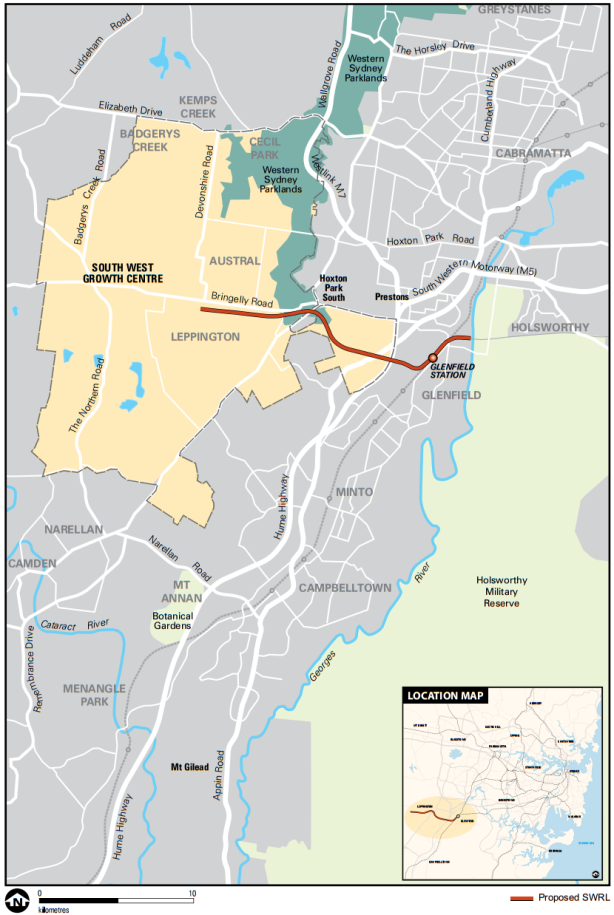

This uses up 6 of the available 10 “slots” on the City Circle (discussed above in spare capacity), leaving 4 unused. This leaves enough spare capacity for when the South West Rail Link comes online in 2016 and Sydney Trains has another major timetable re-write.

“new rail timetables planned for 2013 and 2016” – Source: Transport Master Plan, p. 135

This means that no additional capacity is available for the South Line or Inner West Line in the short to medium term. However, on overcrowding, the problem with these lines appears to be less their average loads (109% and 119%) which are on the low end for Cityrail as a whole, but more their maximum loads (153% and 164%) which are near the top of the list for all the lines. Here the solution seems to be to more evenly spread out services, rather than have long waits between successive trains – which causes overcrowding of some trains even if the average load is quite reasonable. This would certainly be an improvement, though is still less than ideal.

“Following the opening of the Homebush turnback and the introduction of new trains, the Inner West line will see the introduction of a reliable timetable offering higher frequency services. These measures will eliminate the 20 minute service gaps that can occur at some stations during peak periods” – Source: Sydney’s Rail Future, p. 19

A lot of rumours exist about the Western Line and Northern Line, but few things have been officially confirmed. It initially appeared that the government was considering removing direct services for the Richmond Line, sending its trains to Campbelltown via the Cumberland Line, and also for Northern Line trains from Epping via Strathfield, which would terminate at Central Station. However, a draft copy of the 2013 timetable, circulated to Railcorp employees recently, appears to show no stations on these lines will lose direct services to the CBD. Instead, some Western Line trains will continue through to Hornsby via Macquarie Park rather than along the North Shore Line as they do now. This may provide an increase in capacity to the upper Northern Line at the expense of the upper North Shore Line – though this could also be done by trains that terminate shortly after Chatswood, and so see little change in services for the Upper North Shore.

What is more certain is the addition of 2 more trains per hour on the Northern Line starting at Rhodes, a station that has seen its patronage grow strongly in recent years due to surrounding developments. These trains would probably terminate at Central.

“Two additional trains to service the busy North Strathfield to Rhodes corridor will be introduced in the shorter term” – Source: Sydney’s Rail Future, p. 19

The government has also spoken of increasing frequencies on the North Shore Line from 18 to 20 per hour. However, it has not said when it plans to do this, other than it will happen by the time the North West Rail Link (NWRL) opens in 2019. Given the relatively low average loads on the North Shore Line compared to other lines, this makes additional services in 2013 look unlikely.

“Peak period services [on the North Shore Line] will increase from the current 18 trains per hour to 20 trains per hour prior to the new Harbour Crossing” – Source: Sydney’s Rail Future, p. 17

[tweet 304804527931002880 align=’center’]

Finally, the Cumberland Line, which provides a direct link between Parramatta and Liverpool, will return to all day service. The draft timetable suggests it will be half hourly services from 7AM till 7PM.

“Parramatta will be better connected to Liverpool and the south west, with all-day, frequent and reliable Cumberland services” – Source: Sydney’s Rail Future, p. 19

Improvements and remaining problems

If the new timetable does look like this, then it will provide significant improvements to overcrowding on a number of lines. Assuming similar patronage numbers, overcrowding as measured by average loads could drop on the Illawarra Line (123% down to 109%), the Northern Line (143% down to 95%), and the East Hills & Airport Line (127% down to 95%). Sending Western Line trains to Epping via Chatswood could also further alleviate overcrowding on the Northern Line.

Estimated overcrowding by line for October 2013.

Where it does not directly deal with overcrowding is on the Inner West Line, South Line, and Western Line. This may be partly mitigated by some passengers opting to take trains on other lines that have seen increased services, or perhaps via a more even distribution of crowds on trains on the South and Inner West Lines due to shorter headways between trains (as discussed above in Changes in the 2013 Timetable).

Some additional relief could be provided by running some trains into Sydney Terminal at Central Station, or by improvements in signalling allowing more trains to operate per hour. However, the former provides only limited improvements while the latter is both expensive and may take many years to roll out.

Future developments

The NWRL is currently scheduled to begin operation in either 2019 or 2020. Preliminary estimates show this will divert around 19 million passengers per year to it from other lines, presumably mostly from the Western Line. This translates to around 6,000 passengers per hour during the AM peak (using some quick back of the envelope calculations), compared the the current 16,000 passengers that use the Western Line’s 16 suburban trains during the busiest hour in the AM peak. This will have the effect of providing additional capacity on the Western Line (Sector 3) by shifting passengers away from it, rather than expanding its actual capacity.

Once a Second Harbour Rail Crossing is built around 2030 it will link up the NWRL to the Bankstown Line as well as the Illawarra Line through to Hurstville. This will free up space on the City Circle (Sector 2) previously used by Bankstown Line trains as well as space on the Eastern Suburbs Line (Sector 1) previously used by Hurstville trains that will now use the new Harbour Crossing route instead.

Sources

Sydney’s Rail Future, Transport for NSW (June 2012)

Transport Master Plan, Transport for NSW (December 2012)