A metro line connecting Sydney’s CBD to Parramatta is firming as the most likely major rail project to be completed once the currently under construction Sydney Metro opens in 2024. This follows the windfall gains received by the NSW Government in the 99 year lease of its poles and wires, with Daily Telegraph political editor Andrew Clennel citing senior government sources that the highest priority in using the proceeds of the privatisation funds will be a “third Metro line from the CBD to Parramatta — taking pressure off the above-ground rail line which is already near capacity”.

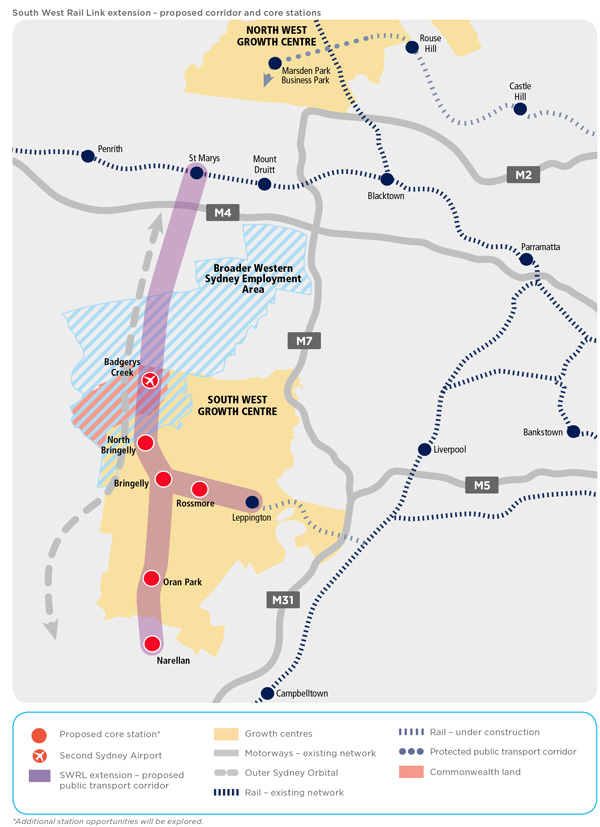

The NSW Government is currently reviewing an unsolicited proposal to build such a line, received in July of this year. The cost is estimated at $10bn and could be partly funded through value capture. This would be possible in sites like the Bays Precinct, Olympic Park, Camellia, and Badgerys Creek. However, it remains uncertain what this means for current plans for a light rail connection from Parramatta to Olympic Park, with suggestions that such a link may be shelved and replaced by a metro rail line.

Transport for NSW subsequently published a discussion paper and is now seeking feedback until 28 October. The discussion paper outlines a number of options, split into Options A-E Western Sydney (mostly connecting Parramatta to the Sydney CBD) and Options 1-6 Western Sydney Airport (connecting the new Western Sydney Airport to the rail network).

Option A, a new western metro-style service, would appear to be the proposal being put forward by the consortium and therefore be the front runner. It is described as:

This line requires a tunnel to be built between Sydney and Parramatta / Westmead with stations located every few kilometres. It could operate as a stand-alone, metro-style, all stops service using high capacity single deck trains with the potential to transport 40,000 extra passengers per hour. It could potentially provide journey times between Sydney and Parramatta of around 30 minutes and relieve some demand on the existing network. This could also support opportunities for new developments at locations such as Olympic Park, Five Dock and The Bays precinct.

Option 5, a direct rail express service from Western Sydney Airport to Parramatta, appears to be the proposal most similar to that being put forward by the consortium and would therefore also be the front runner. However, it involves a 160km/hour express service rather than a metro style service with frequent stops as previous Option A put forward:

This option would include a direct rail express service from the proposed Western Sydney Airport to Parramatta and through to Sydney CBD. This line would require a new tunnel as it approaches Parramatta and from Parramatta through to the Sydney CBD. This service offers the potential for the fastest service between the airport and these two major centres, but would be comparatively expensive to construct. Initial assessments indicate that such a line could achieve journey times of 15 minutes from the proposed Western Sydney Airport to Parramatta and 12 minutes from Parramatta to the Sydney CBD based on a maximum speed of 160 kilometres per hour. While such a service would provide a short travel time to the broader Sydney Basin and CBD, it would not necessarily service the population who are expected to work at and use a Western Sydney Airport in the short-term.

This proposal builds on a March 2016 Parramatta City Council feasability study which suggested a fast train rail link along this corridor, providing a 15 minute rail journey from Parramatta to the Sydney CBD that would also connect Parramatta to a Western Sydney Airport.

Should such a line go ahead, it would pass though and potentially create a new economic corridor for Sydney. The existing “Global Economic Corridor” originally consisted of an zone spanning across Sydney Airport, the Sydney CBD, North Sydney, St Leonards, Chatswood, and Macquarie Park; recently also being expanded to include Norwest Business Park and Parramatta. This new economic corridor would encapsulate Western Sydney Airport, Parramatta, Olympic Park, the Bays District, and the Sydney CBD. This new corridor would pass through Sydney’s 3 cities described by Greater Sydney Commission Chair Lucy Turnbull.

Commentary: How might this line be built?

The Western rail corridor from Parramatta to the Sydney CBD remains one of the most congested in the Sydney network and yet has been seemingly neglected in terms of capacity improvements. Therefore, additional rail capacity is a welcome possibility. What is less certain is how much of it can be paid for with value capture, whether the journey times will be 15 or 30 minutes, and $10bn price tag.

A recent study focused on the Gold Coast Light Rail line found that value capture would be able to pay for only 25% of the capital costs of building the line. Using that as a benchmark suggests that governments will still be liable to fund the majority of the construction costs for major public transport projects. This is also why the windfall gains from recent privatisations is so significant: it makes a project like this possible.

The 15 minute journey time is possible, but unlikely unless the journey is express. The predicted journey times for the 2008 West Metro, which involved a 22km journey that included 10 stations, was 26 minutes. This equates roughly to 45 seconds/km (the equivalent of 80km/hour), plus an additional 1 minute/station. This also corresponds to the estimated journey times for the Sydney Metro currently under construction. So 25-30 minutes would appear a much more realistic journey time than 15 minutes.

Finally, there is the construction costs. Here, a lot depends on how the line is constructed and a number of assumptions will be made. The 2008 West Metro is a good starting point, with the adjustment that it pass through the Bays Precinct and then most likely entering the CBD at Barangaroo. This would involve a similar number of stations, but with a slightly shorter length of perhaps 21km rather than 22km. Curiously, this would effectively see a hybrid of the West Metro and CBD Metro alignments, with the 2008 proposed alignments seen in the map below.

Based on the costs of recent projects, but not taking future inflation into account, a more realistic cost could be just under $11bn for the Sydney CBD to Parramatta portion. From Parramatta to Badgerys Creek, the distance is longer at 26km, but about two thirds of this could be above ground rather than in a tunnel. Additionally, it would likely have fewer stations, probably 4 in total not counting Parramatta. So using the same assumptions, that portion of the project could come in at about $6bn.

That is approximately $17bn, approaching double the $10bn cited by the unsolicited proposal. This should come as no surprise, as unsolicited proposals are in the business of selling their case to the government and thus have an interest in underestimating the potential costs.

Finally there is the question of where to run the line through the CBD. The map accompanying the proposal submitted to the Government, published by the Sydney Morning Herald, suggests connecting the line to the future Sydney Metro at Barangaroo and then another line out from Waterloo out to the soon to be redeveloped Long Bay Prison in Sydney’s South East. This would have the benefit of funneling trains from two separate lines on each end of the central portion of this line, ensuring constant high frequency along the CBD portion of the Sydney Metro.

However, it would also place capacity constraints on the line. For example, it would prevent the Northwest line of the Sydney Metro from increasing its current 15 trains per hour during the peak if the Western line of the Sydney Metro were also to enjoy 15 trains per hour. It would be possible to extend the trains from 6 to 8 carriages, providing a 33% increase in capacity, but not the 167% increase in capacity that is currently possible.

The alternative is to build an additional rail line through the CBD. A second corridor under Sussex St has been reserved for such a future line, in addition to the Pitt St corridor that the current Sydney Metro line will use. Alternatively, the line could cross the CBD in an East-West direction, rather than the typical North-South direction that all the existing rail lines follow. This could potentially provide heavy rail access to Pyrmont or Taylor Square.

Either option would be challenging and disruptive. It would ordinarily also be expensive. But it could be transformational in a way very little else could and NSW has recently come across the billions of dollars necessary for such an endeavour.