Two years since the last state election and two years until the next one, it’s time to evaluate how the O’Farrell government has performed on the issue of transport. Given the scale of time it takes to implement changes and additions to such a large system (a new rail line take almost a decade from inception to opening), it would not be fair to judge the government on things it has not yet had a chance to reform. At the same time, 2 years is enough to take advantage of low hanging fruit, make operational improvements, and begin the process of changing the direction of the heavy ship that is Sydney’s transport system.

This is a long post, so here is the summarised version:

- The good: The government has committed to a Second Harbour Crossing, Gladys Berejikliian is a good Transport Minister, the rollout of integrated ticketing (Opal) is on track, there will be a big increase in train services later this year, the South West Rail Link is running 6 months ahead of schedule, the creation of an integrated transport authority (Transport for NSW) will allow an integrated transport network, the government has prioritised public transport ahead of roads, the government learned from the PPP mistakes of the past, and new transport apps are making getting around easier.

- The bad: Overcrowding on Cityrail is up, on time running on Cityrail is down, no congestion charging, and no committment to a second Sydney airport.

- The uncertain: Integrated fares, sectorisation of the rail network to untangle it, and driverless trains??

The most important parts at this point in time, in my opinion, are a Second Harbour Crossing (good), integrated fares (uncertain), sectorisation (uncertain), creation of Transport for NSW (good), Opal (good), overcrowding (bad), on time running (bad), Transport Minister (good). our good, two uncertain, two bad. The two bad points could be improved with the October 2013 timetable changes, if some hard decisions are made, whereas the two uncertain points will require a decision some time this year. It will be worth revisiting this in 12 months time to see if the government delivers on those four points, but until then I would rate the government as a B overall (on a scale of A to F). This is giving them some benefit of the doubt, based on a good overall performance in other areas. Without the benefit of the doubt, bump that down to a C.

This is obviously quite subjective, so I welcome your thoughts and feedback in the comments section below.

Capacity improvements

The best way to improve capacity into dense employment centres, like the CBD, Parramatta, or Macquarie Park, is with rail, preferably heavy rail. It is pleasing to see, therefore, that the government has committed to a Second Harbour Crossing, a new light rail line down the CBD through to Randwick, and the North West Rail Link (NWRL), in addition to the South West Rail Link (SWRL) and Inner West Light Rail extension, both commenced under the previous government. The Second Harbour Crossing in particular, expensive and opposed by some as necessary given the cost, will result in a 33% increase in capacity across the network by adding a fourth path through the CBD.

The decision to dump the Parramatta to Epping Rail Link (PERL) is unfortunate, but was the right call as the priority right now is with the projects listed above. Similarly, the decision to build the NWRL with smaller and steeper tunnels, thus preventing existing double deck trains from using them, could be seen as short sighted. However, it also guarantees that the line will remain separate from the Cityrail network, opening up the possible benefits of a new operating model that has a lower cost to operate and therefore can provide more frequent services (see: Private sector involvement). It also has the benefit of lower construction costs, which would be very beneficial should the Second Harbour Crossing go under the Harbour, as seems likely.

- Conclusion: A committment to expand the rail network, a Second Harbour Crossing in particular, will improve capacity by 33%. The decision to make the NWRL tunnels narrower and steeper remains controversial.

- Grade: B

Service quality

The Cityrail network, which forms the backbone of transport in Sydney, is under a lot of pressure at the moment. Overcrowing is up, while on time running is down. February was one of the worst months in Cityrail’s history, with 5 major disruptions during peak hour causing a suspension of services, which often spilled over onto other lines in the network. You have to go back 4 years to find operational figures this bad. It urgently needs additional train services to ease overcrowding and a more simplified network to improve reliability.

Interior of a Sydney tram. Overcrowding is up on the Cityrail network. Click on image for higher resolution. (Source: Author)

Part of the cause of these problems is the network that the government inherited. But 2 years in, it is now incumbent on the government to fix it. So far, this has meant 63 new services per week in 2011, and then 44 new services per week in 2012, for a total of 107 new services per week. This is a good start, but baby steps at best. What is really needed is an increase on the scale of the 2005 timetable, which cut 1,350 weekly services. Previously there have not been enough train drivers or rolling stock to do this, and it remains uncertain whether it’s possible now. Older, non-airconditioned trains may need to be used if the government does not order more Waratah trains to increase capacity.

Transport Minister Gladys Berejiklian has continually pointed to October of this year as the moment that a new timetable, re-written from the ground up, will be introduced that features a streamlined network with additional services. But few details have been officially released, though some proposed changes have been leaked. Once that is implemented, it would be worth revisiting this issue. Service is also still better than the horror years of 2003-05. These two factors give the government a slightly more favourable rating than would have otherwise been the case.

There have been some minor improvements that are worth mentioning in passing. Quiet carriages have been introduced and phone reception is now available in the CBD’s underground rail tunnels.

- Conclusion: Overcrowding and reliability are at 4 year lows in the rail network, though there have been minor improvements such as quiet carriages and phone reception. Overall, it’s a poor result.

- Grade: D

Ticketing and fares

The major issues here are the Opal rollout and integrated fares.

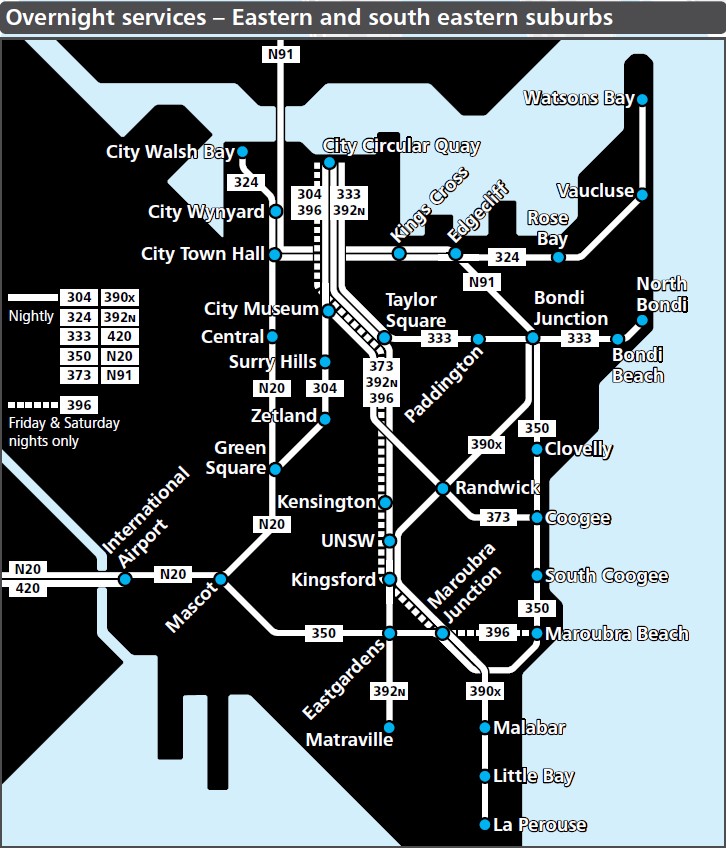

The implementation of Opal appears to be on track, with the new smartcard set to expand to the Manly Ferry on April 8, and then to the Eastern Suburbs and City Circle stations in the second half of 2013. Up to now it appears to have proceeded without any major hiccups, and has gotten further in the rollout than the T-Card did.

There remains little detail on integrated fares other than that cabinet will consider fares at some point in early 2013. This is a potential game changer, and it seems likely that it could be implemented once Opal is fully rolled out.

The government has made a committment to not increase fares beyond CPI unless service levels improve, and has also incorporated the light rail into myZone. Both are positive, though the former is problematic in that it will erode the ability of fares to recover operating costs, as fares only account for about a quarter of the cost to operate Sydney’s transport network.

- Conclusion: Good progress on Opal, but not on integrated fares. Limiting fare increases and putting the light rail on myZone are also some good minor improvements.

- Grade: C

Transport Minister

Gladys Berejiklian has been a good Transport Minister for 2 reasons: she supports public transport and she is a strong advocate of it.

She strikes the right balance between public transport (trains, buses, ferries, trams) and private transport (cars, roads). It’s worth pointing out that, despite numerous claims that this government is pro-car and anti-rail, the current government spends more than half of its transport capital works budget on public transport. It’s also worth remembering that private motor vehicle trips will continue to play a key role in providing mobility to Sydney residents, and therefore the road network should still be expanded. But the focus should be on public transport, as it currently is.

As an aside, this support for public transport is unusual for a politician from the conservative side of politics. But both Ms Berejiklian and the Premier Barry O’Farrell are not your traditional hard conservatives, both more accurately described as moderate pragmatists. They both seem to recognise that congestion is costing the NSW economy money and the best way to improve the situation is to focus on public transport.

The Victorian Liberal Government’s top transport project is a road tunnel under the CBD, while the recently elected WA Liberal Government rejected the opposition’s 75km expansion of the rail network in favour of a short airport rail link and light rail for the inner city with a greater focus on improving the road network. Across the Tasman, the Auckland Transport Blog speaks favourably of conservatives in Australia (though really it’s more a comment on NSW, because as seen this is not a view necessarily shared by Liberal Parties in other states):

“I guess this is what happens when you have a centre-right government that isn’t completely insane in its ideological dislike of public transport…I do wonder why centre-right politicians in Australia don’t seem to have the same ideological dislike of public transport as seems to be the case in New Zealand.” – Mr Anderson, Auckland Transport Blog (23 December 2012)

The other, and arguably more important, reason why Ms Berejiklian is a good Transport Minister is her strong advocacy. It’s not enough to support something if the cabinet or Premier overrule you. And Ms Berejiklian has demonstrated an ability to get her agenda through the cabinet where it’s been needed. She got cabinet to support an expensive Second Harbour Crossing, despite opposition from Infrastructure NSW Chairman Nick Greiner and took the light rail issue to cabinet 3 times until it accepted her preferred option of George St light rail over the CBD bus tunnel. These two major items, along with numerous other minor ones, were not a fait accompli, and are a testament to Ms Berejiklian’s influence.

- Conclusion: Gladys Berejiklian is supporter of and effective advocate for public transport

- Grade: A

Funding, costs and scheduling

Public transport projects in NSW seem to come in over budget and behind schedule all too often. That appears to have been partly continued. The Inner West Light Rail extension has been delayed by 18 months and its cost blown out by $56m, while the cost of the South West Rail Link (SWRL) went from $688m to $2.1bn. However, the SWRL is running ahead of schedule: the new Glenfield Station was completed 4 months ahead of schedule, while the new line is on track to open 6 months early. While this project was started by the previous Labor government, it’s delivery has been overseen by the current Liberal government and that’s what matters. The North West Rail Link has seen some blow outs in costs, but these are tens of millions of dollars in a multi-billion dollar project, so here it’s too early to make any judgement.

On the revenue side, the government has spoken about value capture as a way of funding infrastructure improvement, where property owners whose land values increase because of government built infrastructure contribute to the cost of building it. This is welcome, but no action has yet been taken. It has also openly committed to making users of any new or improved freeways pay tolls to contribute to their construction. This move to a user pays system, where the users of motorways pay for them rather than all taxpayers whether they use them or not, is a welcome one. What is unfortunate, is that the government has refused to introduce congestion charging, as pricing roadspace would allow a more efficient use of it, reducing congestion and the need to build more roads.

- Conclusion: Cost blowouts and delays remain, though a possible early finish to the SWRL is a welcome surprise. Tolling and funding is a mixed bag, but mostly positive.

- Grade: C

Governance

The two big reforms made by the government in the area of governance are the creation of Transport for NSW, which brought all transport related departments and agencies under the one umbrella, and the splitting of Railcorp into Sydney Trains and NSW Trains.

Transport for NSW’s creation is a game changer. By centralising planning into one department, rather than independent “silos” in separate departments that rarely communicate with each other, it will allow transport in Sydney to be fully integrated as one network, rather than a collection of separate networks. This extends to things like timetables and fares, but also adds roads to the mix – changing a transit department into a true transport department. All of this which will allow commuters to get from A to B much more easily than is currently the case. It will make examples like the following a thing of the past:

“For example, a customer could travel from St Ives to Sydney, via a private bus to Turramurra, a Cityrail train and walking along the city streets… The journey requires 2 separate tickets and therefore revenue streams, which never meet. The two vehicles are owned, maintained and driven by vastly different staff working for different silos.

The station facility is provided by Cityrail. If they’ve thought to accommdate the bus in the design of the facility, it would be the exception rather than the norm. The timetabling, if it is done at all, would be by a third silo in a distant building, remote from the reality of what’s happening.” – Riccardo, Integrated transport planning – what is it really? (11 June, 2011)

The Transport Master Plan put a great deal of emphasis on moving towards an integrated network, one where it would be much more common practice to take a feeder bus to a transport interchange and then take train, tram, or another bus to your final destination, with all coming frequently and all day, in order to maximise mobility. This would be a big improvement on the current network design, which is designed more around a single seat trip to the CBD than on connections to get you from anywhere to everywhere. However, this will be difficult to implement without integrated fares (discussed above), as currently commuters are penalised for making a transfer as though it is a premium service, when really it’s an inconvenience.

Evidence of the benefits of centralised planning can be seen in the recent decision to house metrobuses in separate depots in order to minimise dead running. This was not previously possible, as planning was done at the depot level, and so shifting buses from one depot to another was not feasible.

A Metrobus on George St in the Sydney CBD. Click on image for higher resolution. (Source: Author)

The changes to Railcorp are not set to occur until July 1 of this year, so the jury is still out on that.

- Conclusion: The creation of Transport for NSW, centralising the planning function and creating a true transport department.

- Grade: A

Planning

NSW has had no lack of plans in recent years, if anything it’s had the problem of too many plans but not enough action. When it comes to just planning, the government had 2 competing visions: the Transport Master Plan from Transport for NSW and the State Infrastructure Strategy from Infrastructure NSW.

To its credit, every time the two plans disagreed, the state government sided with the Transport Master Plan every time. That means it has committed to building a Second Harbour Crossing for the rail network and light rail down George Street rather than the ill-fated bus tunnel idea.

It also dogmatically refused to commit to a light rail line to Randwick until a feasibility study was completed, but then got totally behind the project once it was completed and put before cabinet.

That is not to say that there aren’t concerns about the planning process. For example, the government has committed to the Second Harbour Crossing before having done enough work into it to name a cost or set a timetable for its completion. It was this sort of behaviour that contributed to the $500m spent on the aborted Rozelle Metro by the previous government.

- Conclusion: The government has sided with Transport for NSW, rather than Infrastructure NSW, leading to a greater focus on public transport, rather than private transport. However, it has a mixed history of committing to projects before having done its homework.

- Grade: B

Private sector involvement

The failure of PPPs like the Airport Line as well as the Cross City and Lane Cove Tunnels mean that government’s should approach private sector involvement with caution. But that does not mean that it should avoid it entirely.

In NSW, the government has opted to adopt the WA model, rather than the Victorian model. In WA, the government plans and owns the network, but puts the operation of various lines or regions out to tender, allowing competitive practice to drive down costs while maintaining a minimum contractual level of service. The government then pays the operator, but keeps all fares, ensuring that the operator can increase profits only by operating more efficiently, rather than by cutting service. The Victorian model sees the operators keep farebox revenue, which is then topped up by a government subsidy. The disadvantage of the Victorian model is that the operator can increase profits by cutting services with low patronage, even if these services are part of an overall network such as feeder buses.

The chosen model has proven successful in NSW, having been used on the bus network for almost a decade. It allowed the government to put some bus contracts out to tender, resulting in $18m of annual savings for the tax payer. It has also recently been expanded, when Sydney Ferries being franchised last year. The NWRL is also planned to be privately operated, while the Sydney light rail line was recently re-purchased by the government but will remain operated by a private company.

Sydney Ferries were franchised in 2012. (Source: Author)

The decision to turn the NWRL into a completely separate and privately operated line, but one where commuters still pay the same fare as if they were on a Cityrail train, has the potential to finally stem the bleeding in Cityrail’s costs, perhaps through the use of driverless trains that would allow very high all day frequencies.

The recently introduced unsolicited proposal process has also allowed a proposal for an M2-F3 link to be constructed by the private sector at no cost to the taxpayer. While the outcome is uncertain, the process has been shown to work, and is a great way to increase the stock of infrastructure in Sydney. (Setting aside the involvement of this process for another Sydney Casino, which has raised some controversy.)

- Conclusion: The government has learned from the bad PPPs of the past and appears to be using private sector involvement as a means, rather than as an ends.

- Grade: A

Second Sydney airport

The current government has not only ruled out the preferred site of Badgerys Creek for a second airport, it has ruled out a second airport altogether, suggesting that a high speed rail line to Canberra airport could be used as a substitute. Not only is this unlikely to happen, given the high costs involved, but it means passing up on the opportunity to bring jobs to Western Sydney and revitalise its economy, which currently has a huge jobs shortfall that is only predicted to increase.

Current and proposed Sydney airports. Click on image for higher resolution. (Source: Google Maps)

Given the lack of support for a second airport, it is then disappointing that the government has not sought to reduce or elimiate the access fee for users of the airport train stations in order to ease the ground transport congestion around the airport, cited as the biggest constraint on Sydney’s Kingsford-Smith Airport at the moment.

- Conclusion: The government does not support a second airport, and has not done enough to improve the capacity of the existing airport.

- Grade: F

Transport apps

The makers of transport apps have seen an increase in the amount of transport data available to them. This has allowed for Google Transit to expand to all forms of public transport (previously it was just light rail and the monorail), and has also now included bike paths (though it seems Google did this on its own, rather than with help from the state government). More recently real time bus data was provided for STA buses, and will hopefully later be extended to all buses and also trains.

- Conclusion: The government has been proactive in improving transport information to commuters by involving third party developers.

- Grade: A